Ear Reconstruction

Introduction

The ear is a mostly decorative structure of intricate cartilage folds covered by skin. Its aesthetic quality is extremely important. About 1 in 6000 children are born without one or both ears, a condition known as microtia. Others lose an ear or part of it in later life. because of trauma, cancer or other disease.

The loss of the ear in whole or in part can cause psychological distress out of proportion to its size. In some patients, particularly teenagers, it can cause serious behaviour problems and mood swings. Lack of an ear is also a disability - the ear supports glasses, sunglasses, blue-tooth headsets and headphones.

The ear components are difficult to mimic, and reconstruction, especially after destruction or resection of cancer, is a challenging task. Ear reconstruction has suffered a poor reputation born of poor results in the past, but in the last decade, much progress has been made.

Some do not wish to have the defect reconstructed. For the rest, there are two reconstructive options - to have the ear rebuilt from their own tissues (autogenous ear reconstruction) or to have a prosthetic or false ear anchored to the bone of the side of the head by titanium fixtures (a bone anchored prosthesis) using a technique called osseointegration pioneered by Branemark in Sweden. A number of patients are unable to tolerate the idea of something false attached to them. Some who have a prosthetic reconstruction were unaware that autogenous reconstruction was a possibility.

Main indications

Trauma (especially bite injuries)

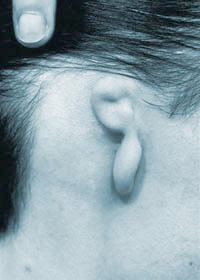

Loss of the ear through trauma seems to be more common than ever before. Irate boxers, Saturday night violence and dog bites have all made headlines. Most trauma cases are bite injuries but a few are due to sharp lacerations. Even an air bag which expands in a car with a broken window can cause amputation of the ear. Attempts to replant ears in the emergency setting often yield poor results and even in experienced hands, there is little chance of restoring blood supply using microsurgery. After a surgical tidy-up, the raw area is best left to heal and the missing area reconstructed at a later date.

A human bite injury pre-op

A human bite injury pre-op  After surgery - missing segment reconstructed

After surgery - missing segment reconstructed

Burns

Burned ears often develop a lingering inflammation of the cartilage (chondritis) which can result in severe collapse and destruction. Acid burns, in particular, can close the ear canal. The skin behind the ear is often preserved and this, if pliable and unscarred, is useful for the reconstruction. The fleshy lobe is also often preserved and this too can be useful.

Burn injury pre-op

Burn injury pre-op  Burn injury post-op

Burn injury post-op

Cancer

The ears are a common site for skin tumours; the tops of the ears are often exposed to sun but not often protected by sun screen, the backs of the ears and rubbed by spectacles and sunglasses, and both the backs of the ears and the conchal bowl of the ear can be irritated by hearing aids and in-ear hearing devices.

A red, scaly or bleeding area which will not heal or keeps reappearing is best removed and the tissue sent to the laboratory for investigation. Such surgery need not spoil the appearance of the ear, but the earlier an ear tumour is removed, the easier the ear is to reconstruct.

Usually, only very neglected ear cancers require a full ear reconstruction using costal cartilage. The majority can be excised and the defects repaired with local grafts and flaps.

Microtia and Anotia

Microtia (a small ear) and Anotia (a totally missing ear) are conditions which are present and obvious at birth.

It is very important to resist attempts at surgery to improve the appearance of the ear or scalp area before definitive reconstruction, as the blood supply to the new ear can be irreparably damaged and the results compromised.

Actor and model Sasha Gardner

Actor and model Sasha Gardner

TYPES OF Reconstruction

Autogenous reconstruction is worthwhile only if great attention is paid to fine detail. In addition to providing a realistic shape, it is important to leave the ear canal unaffected, to provide support for spectacles and a lobe for earrings. The ear must be positioned at the correct level and with a slight posterior slope to match the opposite normal ear. Some patients may need reconstruction of both ears.

If the missing area is small, then a conchal cartilage graft (a graft from the cartilage of the other ear) may suffice. However, for major defects, a detailed framework, which mimics the folds of a normal ear, is necessary. There are two essential elements for a good ear reconstruction - an accurate framework and loose and pliable skin of good quality to cover it. Scarred skin is not pliable, but usually thick and inelastic and it can mask the details of the framework and spoil the result, so a more complex ear reconstruction technique is required.

Frameworks made from artificial materials, such as preformed silicone or Medpore shapes, can often provide a realistic result but there is a very significant risk of late extrusion of the framework when minor trauma has lead to infection. As a result, few surgeons choose this route. Those who do quite rightly point out that there is no additional scar or discomfort caused by the donor site on the chest. Those who do not point out that the donor site scar is minimal, and the discomfort temporary.

Minimal chest scarring from rib removal

Minimal chest scarring from rib removal  Minimal scarring at donor skin graft site on thigh

Minimal scarring at donor skin graft site on thigh The gold standard technique remains the use of costal cartilage (taken from a rib) to assemble a framework. This framework, made of living tissue, will repair itself in the event of minor trauma and, in the long term, is much less prone to infection or extrusion, although a little stiffer than the normal cartilage of the opposite ear.

1. Simple Autogenous Reconstruction

If the tissues have not been damaged by previous trauma or surgery, it is possible to fashion a completely new ear in two operations six months apart. In some circumstances, the two stages can be rolled into one, with a minor procedure later.

The first stage of a simple autogenous ear reconstruction takes between four and five hours under general anaesthetic. The first step is to map the shape of the normal opposite ear. When both ears are lost, such as in burned patients, an ear shape can be copied from a willing relative. The shape is drawn on a see-through plastic sheet, then cut out to leave a template which can be sterilised for use throughout surgery.

A small incision is made in the chest wall at the edge of the ribcage of the opposite side. At the end of the operation, a small drain is left in this wound so that pain-relieving medicine can be given directly into the area. A small piece of cartilage is usually stored here to be used to jack out the ear at the second stage.

Marking the new ear position pre-op

Marking the new ear position pre-op  Immediately after surgery, drains in place

Immediately after surgery, drains in place  The sections of rib cartilage removed from the chest

The sections of rib cartilage removed from the chest  Rib cartilage sections carved and assembled into new framework to match template

Rib cartilage sections carved and assembled into new framework to match template The material used for the framework, known as costal cartilage, joins the ribs to the breastbone. It is white in colour, and usually fairly easy to carve. If an entire ear is missing, it is assembled from several carved components, one for the rim, one for the main part of the ear, and separate pieces to resemble the individual ridges and valleys that make a realistic ear shape. The finished framework is then inserted under the skin on the side of the head, blending with any ear elements which might be useful. The skin is draped over the framework to form an airtight seal and suction drains are used to draw the skin into its folds. By the end of the operation, a contoured framework in the shape of an ear sits in the right place on the side of the head, albeit almost flat against it. Suction is applied continually for up to five days so that the ear shape persists.

Before surgery

Before surgery  Immediately after the first stage of surgery, drains in place

Immediately after the first stage of surgery, drains in place  Before Surgery

Before Surgery  After the first stage of surgery

After the first stage of surgery About six months after the first stage, the circulation to the zone of reconstruction has become established, and the second stage can proceed. The new ear is lifted from the side of the head, so that it projects normally, with a groove behind it. The block of costal cartilage stored beneath the scar in the chest wall is used to maintain projection, and the two raw surfaces, one behind the ear and one on the side of the head, are covered by a mixture of grafts (usually from the thigh) and skin flaps harvested locally.

Second stage surgery takes almost two hours, again under general anaesthetic. Scarring is usually minimal.

Before surgery

Before surgery  10 days after the second stage of surgery

10 days after the second stage of surgery

Complex Autogenous Reconstruction

For tissues which have been damaged, it is sometimes necessary to first increase the amount of skin cover by inserting a tissue expander before the first stage, or by raising a temporoparietal fascial flap at the time of the first stage surgery. If neither option is available then a free flap or a bone anchored prosthesis is required.

Of the first 250 reconstructions performed for ear loss (as opposed to microtia), 60% resulted from bites, road traffic accidents and shootings, 13% from burns, 11% from failed surgery to set back prominent ears, and 5% from infected piercings. Some patients are referred after failed attempts at reconstruction and these are especially challenging. In some of these, a bone anchored prosthesis is the only option. It is very important to resist attempts at surgery to improve the appearance of the ear or scalp area before definitive reconstruction, as the blood supply to the new ear can be irreparably damaged and the results compromised.

Tissue expansion

When there is an inadequate amount of pliable skin to cover the framework, an initial procedure to insert a tissue expander may be necessary. A large expander, which looks like a deflated balloon with a tube to inflate it, is introduced through a small incision some distance away from the site of the ear reconstruction. Expansion, using saline injections into a valve on the inflating tube, is begun the week after insertion and continues at weekly intervals for about eight weeks until the skin is stretched enough.

Tissue expansion after traumatic amputation

Tissue expansion after traumatic amputation  Immediately after surgery

Immediately after surgery  Reconstruction of a ear removed for melanoma

Reconstruction of a ear removed for melanoma  During tissue expansion

During tissue expansion  the ear framework carved

the ear framework carved  The result after the first stage

The result after the first stage Temporoparietal fascial flap

This large flap of tissue is ideal for framework cover when local tissues are poor. Lying beneath the scalp, immediately underneath the hair follicles, it has a rich blood supply. Skin grafts from the scalp are placed on top of the fascia complete the skin cover.

An Iraqi victim of torture

An Iraqi victim of torture  Pre-op mark-up of the skin

Pre-op mark-up of the skin  TP flap applied during surgery

TP flap applied during surgery  The final result at around 2 months post-op

The final result at around 2 months post-op  Complete avulsion of the ear

Complete avulsion of the ear  Pre-op markings on the ear and scalp

Pre-op markings on the ear and scalp  the ear framework carved

the ear framework carved  The result after the first stage

The result after the first stage

Free flaps

When trauma or prior surgery has destroyed local tissues, the temporoparietal fascia cannot be used, and autogenous tissue reconstruction is only possible if a free fascial flap is raised. In such circumstances, the complexity of the surgery and the quality of the outcome need to be realistically outlined to the patient. A bone-anchored prosthesis is one option but a number of patients are unable to tolerate the idea of something false attached to them.

The overall shape of the ear will be hidden by post-operative swelling for many weeks.

Bone anchored prostheses

The prosthetic technique also requires two stages, again both under general anaesthetic. The first involves removal of any ear remnant and the placement of two or three small titanium implants into the bone on the side of the head. These metal fixtures become firmly embedded into the bone and at a second stage, metal “abutments” are attached to the implants.

Once all has healed, extensions can be attached to the abutments and a false ear can be attached, in turn, either by a system of clips or magnets. A good prosthesis will last approximately eighteen months before it requires replacement. It should generally be removed at night so that the ear and the area around the abutments can be very carefully cleaned.

Prosthetic reconstruction is preferred when the tissues or the blood supply at the site of the missing ear have been very badly damaged, either by trauma, disease or by previous surgery. As results from autogenous ear reconstruction improve, it is unusual to choose a prosthesis unless there is no other option.

A number of patients with a prosthetic ear, even those with very good results, seek advice about the possibility of converting to the autogenous option. Many of these naturally dislike the idea of detachable body parts.

RELEVANT PUBLICATIONS

Books

Gault DT

Total Reconstruction of the Pinna - a chapter for Scott Brown's Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, 7th Edition Arnold

Gault DT

Reconstruction of the ear – a chapter for Principles and Practice of Head and Neck Oncology Editors Peter Rhys Evans, Patrick Gullane & Paul Montgomery. Martin Dunitz 2003

Winner of George Davey Howells Memorial Prize for most distinguished published contribution to the advancement of Otolaryngology during the preceding five years.

Academic papers

Chana JS, Grobbelaar AO & Gault DT. (1997)

Tissue expansion as an adjunct to reconstruction of congenital and acquired auricular deformities.

British Journal of Plastic Surgery 50:456-462

Harris P, Ladhani K, Das Gupta R and Gault DT. (1999)

Reconstruction of Acquired Subtotal Ear Defects with Autogenous Costal Cartilage.

British Journal of Plastic Surgery 52: 268-275.

Gault DT. (1998)

Ear Reconstruction : Pitfalls and Tips

Face 6: 15-16

Sabbagh W, Withey S and Gault DT (1999)

A simple alternative to ear reconstruction (letter)

British Journal of Plastic Surgery 52:80-81.

Chana JS, Grobbelaar AO and Gault DT (1998)

Tissue expansion: a useful adjunct to auricular reconstruction

Face 6: 65-68.

Gault D. (1999)

Reconstruction for microtia.

Journal of Laryngology and Otology Supplement no 23. Vol 113, page 27.

Botma M, Aymat A, Gault D, Albert D

Rib graft reconstruction vs Osseointegrated prosthesis for microtia: A significant change in patient preference.

Clinical Otolaryngology. 2001, 26, 274-277

Cicchetti S, Skillman J and Gault D

Piercing the upper ear: a simple infection, a difficult reconstruction

British Journal of Plastic Surgery 2002, 55, 194-197

Lawson K, Waterhouse N, Gault DT, Calvert ML, Botma M, Ng T.

Is hemifacial microsomia linked to multiple maternities?

British Journal of Plastic Surgery 2002 55, 474-478

Sabbagh W and Gault D

Location, location, location

Journal of Laryngology and Otology; 2004 118: 738-740

Vadodaria S, Mowatt D , Giblin V, Gault D

Mastering ear cartilage sculpture: the vegetarian option

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 116(7), Dec 2005 2043-2044

Bajaj Y, Wyatt M, Gault D, Bailey M, Albert DM

How we do it: BAHA positioning in patients with microtia requiring auricular reconstruction

Clinical Otolaryngology 2005 30: 468-471.

Horlock N, Vogelin E, Bradbury ET, Grobbelaar AO, Gault DT

Psychosocial outcome of patients after ear reconstruction – a retrospective study of 62 patients.

Annals of Plastic Surgery 54: (5): 517-524 2005

Gore S, Myers S, Gault D

Mirror ear: a reconstructive technique for substantial tragal anomalies or polyotia

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery 59, 499-504 2006

Beckett KS and Gault D

Operating in an eczematous surgical field; Don’t be rash, delay surgery to avoid infective complications

Accepted by the British Journal of Plastic Surgery 2006